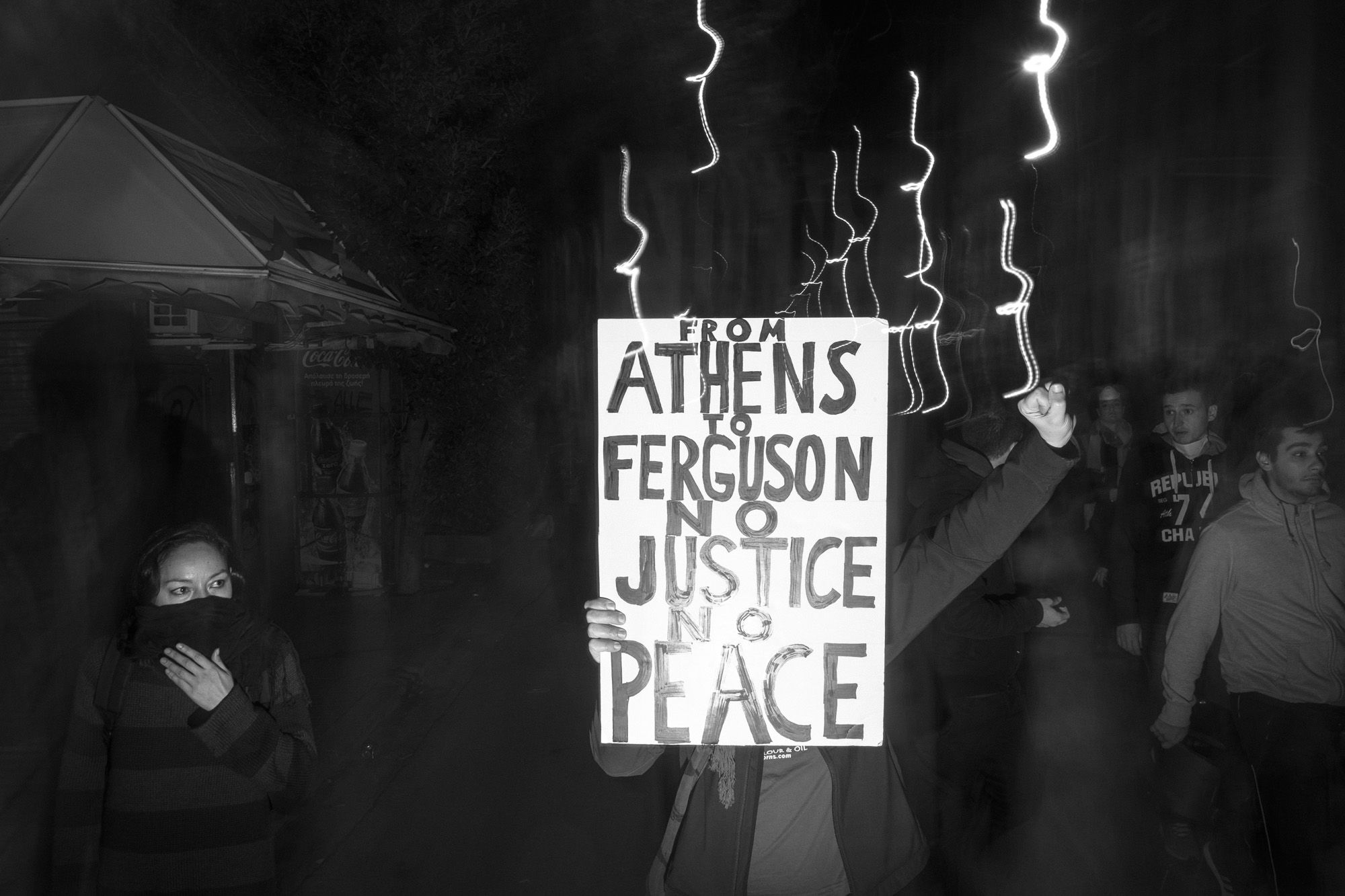

When the December 6 protest in central Athens erupted into all-out street violence, I was watching it unfold from a street corner in Omonia.

It was 2014. 8,000 young protesters packed the downtown square, chanting “cops, pigs, murderers” over the sound of breaking glass. Several of them were taking bats to buildings. The smell of burning refuse hung on the night air as a police helicopter circled overhead.

At an intersection between a melted bin and a shattered storefront, a boy in a puffer jacket bashed a traffic light with a stick until it collapsed and died.

“Bad traffic light! Baaad, bad traffic light!” someone commented.

I scouted the area. In a doorway on a side-street, ‘casually dressed’ undercover police, their earpieces and nervous demeanour giving them away, awaited instructions. Further out, a group of riot cops gathered in an alley, wide-eyed and poised to act. Their leader shouted into his walkie-talkie. He sounded frantic.

* * *

An hour later the square was empty, cleared by tear gas and water cannons. The clashes had moved east, into the anarchist area of Exarchia. Several young men were in police custody; many more were bloodied and bruised.

Rinse and repeat

The ostensible goal of this protest had been to mark the sixth anniversary of the killing of Alexandros Grigoropoulos. The unarmed 15-year-old had been shot by a policeman, Epaminondas Korkoneas, in a deplorable act of state violence, triggering nationwide unrest.

And like those protests that came before and after in the most volatile years of the Greek economic crisis, it had followed a familiar script.

The aftermath, too, was predictable. The same words were written in tweets, blogposts and media outlets: crowd sizes, detentions, the worst of the violence and vandalism. The same pictures published, from onlookers and photojournalists after rights had been secured and financial agreements made: banners, flames, beatings, someone's dog who came along. And the same accusations lobbed from each side: who started what, the extent of the brutality, why an onlooker got hit.

But the next day? Nothing had changed. There was no detailed look at what happened to Alexandros in 2008; no mention of the perpetrators; no calls for police reform. The message of the protest was lost – if it had ever been there.

A journalist friend told me that at the height of the Greek crisis, there were 12 protests a day. All of them resulted in zero -- zero -- policy change.

How could the protest organisers have done things differently?

Going vanilla

A lot of people who protest against the status quo aren't willing to protest against the status quo of protest.

–Micah White, Occupy Wall Street organiser

Let's agree that the main purpose of protest is to raise awareness of your demands for change. (There are other byproducts of protests, like building an activist team, that I'll touch on in a future post.)

Presumably, then, you want your action to create headlines and social media energy. So your demands become impossible to ignore.

If you plan to achieve this with a vanilla protest action – marching from point A to point B with banners – you're making at least one of these bets:

- many people will attend (a photo of a sea of people)

- there will be serious, noteworthy violence (a photo of riot cops vs protesters, or vandalism)

The first is unlikely. The second is high risk, and communicates only one thing: 'we're angry'.

Let's explore a different model – of peaceful protest – that could get better returns.

Some best practice

As Martin Luther King advocated, provide "creative tension". Some examples:

Ducks

Radomir Lazovic and Don't Drown Belgrade protested government corruption by bringing a huge inflatable duck to demonstrations. The duck became a metaphor for Establishment fraud. 'As long as the lies grow, the duck will grow', said the movement.

Soon, the duck started appearing all over the city. Don't Drown Belgrade used it in their campaign materials. The duck became iconic.

Schmucks

You don't always need people for your protest. The Womens' Equality Party in the UK recently wanted to push the government to launch an inquiry into mysogyny within the police force. They put up fake 'serious incident' signs using actual leaked text messages between policemen, which drew headlines and captured social media attention.

Trucks

Sometimes, placards aren't enough. The 'direct action' toolbox is vast: from sit-ins and pickets to occupations and blockades.

See the ongoing truckers' blockade in Canada against COVID19 vaccine mandates. They made their demands difficult to ignore by shutting off vital links between the United States and Canada, and causing major economic disruption. The blockade is now in headlines the world over, and has spread to other countries.

Need more inspiration? See Beautiful Trouble, Actipedia and GNAD for case studies. And check out Srdja Popovic's book, "Blueprint for Revolution".

See also: strengthening your campaign material with great typography and storytelling, quick-and-dirty media skills, and exploiting the media's biases.

Cover it yourself

If you can get enough people together, don't just perform the action – sell it in, too. Concretely:

Before protest

- Plan actions that make compelling images while communicating what you want (ideally proposals)

- Build a list of your targets – media/influencers

At protest

After protest

- Publish your material on social media; pitch material to targets

Conclusion

A vanilla protest action – marching from A to B with banners – is the result of people failing to organise properly.

There are a few reasons you might protest, but the overarching one is to make your demands impossible to ignore. So consider:

When you protest, what do you want the world to hear?

If it’s ‘we’re angry’, keep on shouting and fighting and burning.

But if it’s something more nuanced, more constructive, and if you want to have an impact... find a creative way to say it.