Origin myths

In my previous life as a PR consultant to technology companies, I developed ‘origin stories’ for clients.

These are narratives that explain why a business was founded. You’ve surely seen them on the ‘about’ pages of company websites, or in their product material. Things like this:

Jan Koum, a Ukrainian immigrant, struggled with poverty and the high cost of calling overseas. So he created WhatsApp, a messaging app that allows free communication over the internet.

and this:

While traveling in Argentina, Blake Mycoskie was moved by the poverty and health issues he witnessed due to a lack of proper footwear. This led him to start Tom's Shoes, a company that would match every pair of shoes purchased with a pair of new shoes given to a child in need.

and this:

Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia couldn't afford the rent on their San Francisco apartment. To make ends meet, they turned their loft into a lodging space, which laid the groundwork for what would become Airbnb.

The origin stories were typically embellished versions of the truth. Which usually went like this: someone saw a market opportunity, and built a company to capitalise on it.

Nonetheless, origin stories were (and still are) remarkably effective at generating sales and customer loyalty. Because they communicate a founder’s journey that mirrors the customer’s own – that of a regular person with a problem.

To which, of course, the company offers the solution.

Why am I talking about corporate origin stories on an activism blog? Because they use the most compelling and credible archetype in advocacy: the Concerned Citizen.

And just as origin stories humanise companies and their missions, this archetype can bring authenticity and relatability to your activism, too.

Compelling, credible, relatable

Erin Brockovich and Edward Snowden

Concerned Citizens are the purest participants in activist discourse. They’re not professional activists; their salaries and identities don’t depend on their advocacy. They’re involved for only one reason: because they care.

And thus, Concerned Citizens are compelling and credible. Because unlike the specialised activist, their concerns mirror those of the broader public.

Like Erin Brockovich, the single mother who brought a contaminated water case against a powerful company in her town in the 1990s – and won.

Or Edward Snowden, the computer analyst who saw up close how the US spied on its own citizens. And in 2013, blew the whistle on the whole programme.

(Sure, with time these people’s public identities became synonymous with their activism. But that wasn’t how their stories began.)

Conspicuous specialists are less believable

Here’s an illustration of why Concerned Citizens are so compelling.

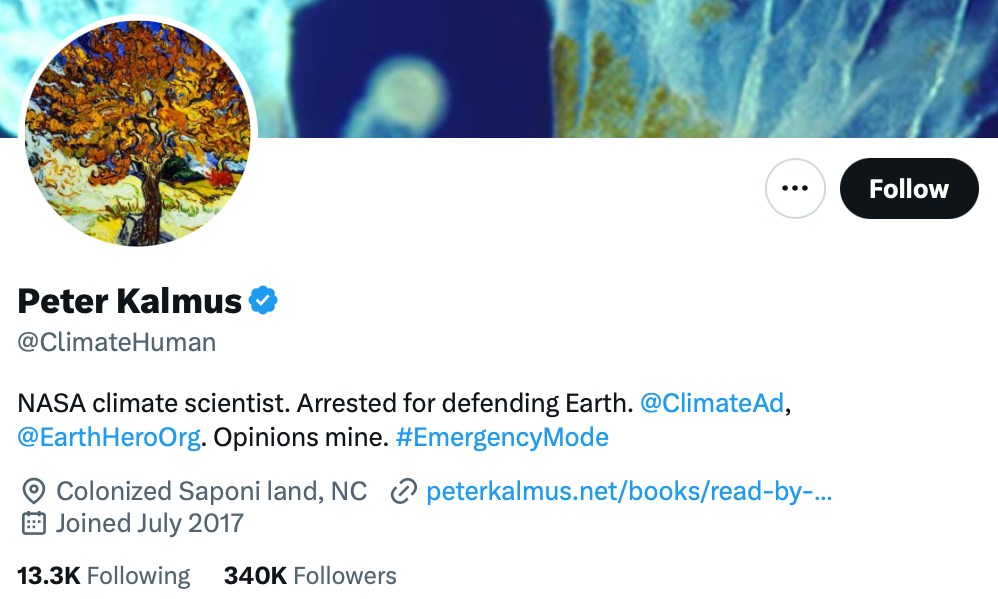

Imagine your social media feed is alight with an alarming piece of climate research. You delve into its origins and find out it was propagated by a certain Peter Kalmus, a scientist based in the US.

You check out his profile. And discover his entire persona is imbued with climate activism. It’s his livelihood, his online identity, his hashtags... even his Twitter handle.

Doesn't the study that Peter shared now seem less credible to you? By putting it out there, he is acting just as you might expect — in line with his persona as an #activist.

I’m willing to bet that the research would be far more compelling if it came from, say, a group of residents who are experiencing climate change first-hand. Like fishermen in the Gulf of Maine, or community leaders in the Pacific Islands. Or indigenous tribes in the Amazon.

In other words, people whose identities are not bound with their activism. Who have nothing to gain from it beyond a resolution to the problem.

Provenance and intention

I don’t mean to pick on Peter (and to be honest, I feel a bit bad about it). Activists like him are probably earnest; they may be doing good work. And they can play an important role in the discourse.

But in this environment, the laser focus of specialist activists on a single issue, their overt stance as a proud warrior for the cause… make these people less credible for engaging a diverse audience.

I think this is because we’re in a cultural moment where the source and the motivation behind information hold immense weight:

- Trust in ‘experts’ is dwindling. Expert bias is real, and people are onto it.

- Obvious propaganda is repelling. And since we’re bombarded with more messages than ever, we’re hyper-vigilant to attempts at persuasion from others.

- Identity is paramount. Our online posts say much more than ‘look at this’. They’re declarations of identity: “this is who I am, this is what I believe”

- We scrutinise intentions. Particularly when people are making a living from their advocacy (which in extreme cases, can lead to accusations of grift)

This landscape doesn’t just affect individual activists. NGOs, too, face a similar predicament. Their funding, their relevance, their survival are tethered to the issues they champion. And everyone knows it. Intention matters.

Put forward the concerned citizen

So as a smart activist, it makes sense to distance yourself from specialisation as much as you can. And instead leverage the Concerned Citizen archetype.

I’m not suggesting being dishonest, like my corporate clients. Rather, I’m proposing you make a strategic emphasis.

Shout about why you got involved in the cause. Highlight the personal stories and motivations of your supporters in your campaign material. Position your campaign, to the outside world, as founded and run predominantly by Concerned Citizens.

Don’t let your cause dominate your identity, but instead put part of your identity to work for it.

TL;DR

Being a conspicuous activist, whose profile is wedded to a single cause day after day, makes your advocacy less authentic.

Instead, you can tap into what businesses have used for centuries: the archetype of the Concerned Citizen; the person who takes up the cause because they care. Emphasise this wherever you can, starting with your own personal story.

This offers a sustainable, credible approach. Especially in today’s discourse, where the provenance and intention of messages matter more than ever.