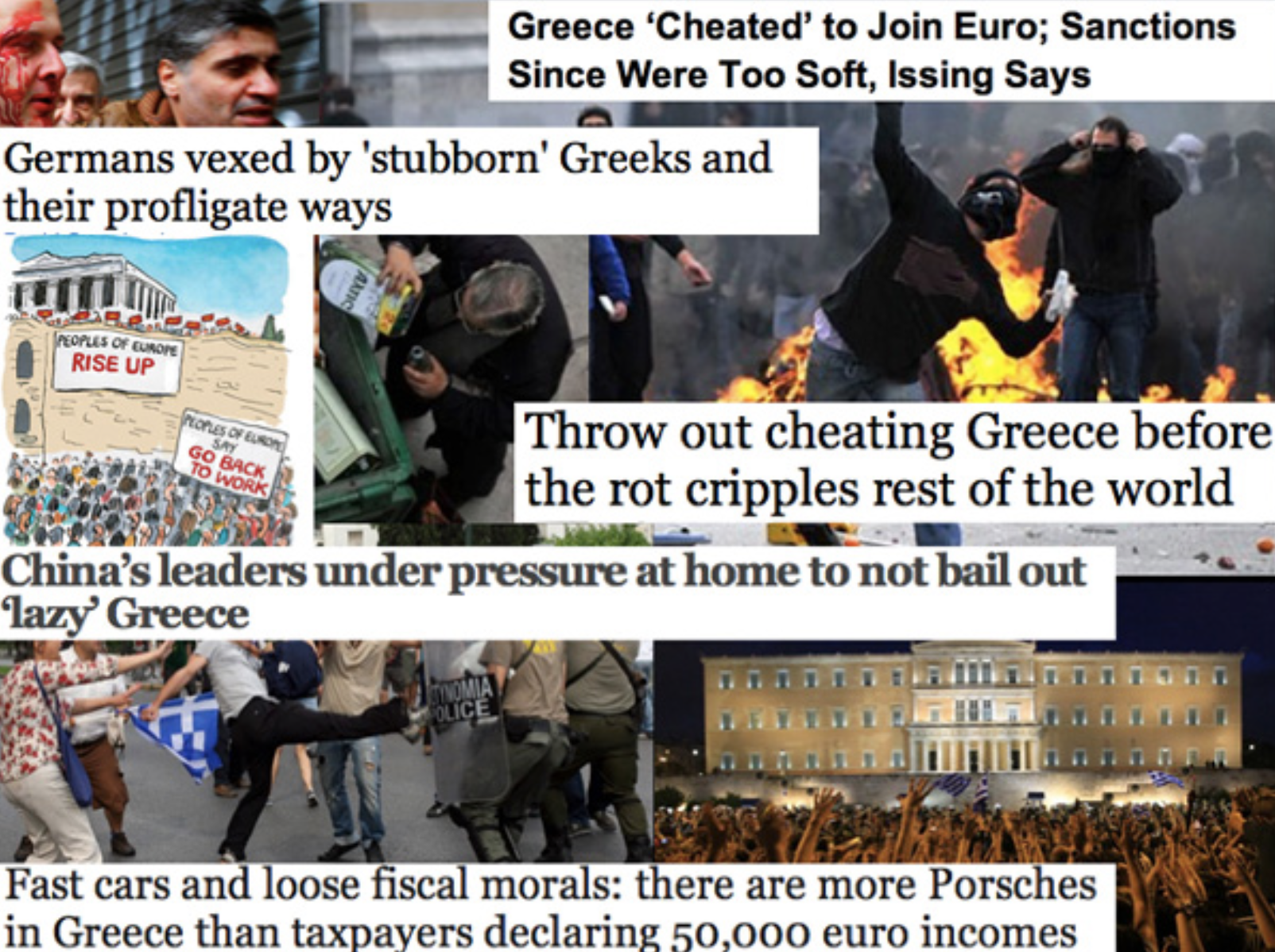

At the height of the Greek economic crisis in 2012, a nasty set of stereotypes started to appear in international media. The idea that Greeks were lazy, dishonest, corrupt and other awful things became a hardened narrative in the pages of ‘serious’ press. Stuff like this:

Now, Greece is my adopted country. My wife is Greek, my kids are Greek. There was little truth to these stereotypes. And the fact that they were floating out there unchallenged made me mad.

So I invited a few friends to a bar for a brainstorm to explore what we could do. I asked them to invite anyone they knew who could be interested.

30 people showed up to the meeting that Saturday afternoon in March. Many of them had never done activism before; most had never met. But they all agreed that the negative stereotypes of Greeks in international media, made them mad too. And they wanted to act.

The bar’s name was Omikron. A campaign called Omikron Project was born.

Omikron Project was active for over three years. And thanks to the brilliant team of volunteers who dedicated their time, the campaign had good results. We made some productions we were proud of, generated a wave of media coverage, learned a lot, and had fun while we were at it.

But Omikron was a particularly valuable experience for me, because it taught me how to build an activist team out of nothing. And unless you’re a lone wolf activist, before you can start planning your campaign, it helps to have a team behind you.

So that’s what we’ll focus on here: How to convince a group of strangers to become collaborators, around a cause you all believe in.

Even in a pandemic, when you might not be able to invite a load of people to a bar.

It’s easier than you think.

Step 1: The invitation

Schedule a Zoom meeting

The world of work has been up-ended by COVID. The tools and the culture are now at the point where videoconferencing is a medium of choice, accessible to all.

So instead of bringing people together in a bar for a brainstorm, we can do it on a Zoom call1.

Pick a time when you think people can make it. Then schedule the meeting, ideally with your Personal Meeting ID2.

Spell out your issue, and make it short

Describe what’s making you mad, in less than 100 words. Use a few examples to illustrate it. Imagine you’re explaining the issue to someone who has never heard of it before.

For example, here’s the body of the original email that spawned Omikron Project:

OK, Greece has enormous political, economic and social problems. But on top of this crisis, the Greek people are being attacked in the global media and online, on a daily basis, with headlines and images like these. [See graphic above.]

Or, here’s how we described the issue for a recent project to save an old stadium in Llubjana, that we worked on with the Campaign Accelerator team at DiEM25:

The Plecnik stadium in Llubjana, built in 1925, is part of Slovenia’s national heritage. Plans are underway to transform the site into a luxury park of skyscrapers, malls and casinos. This ‘renovation’ is headed by a local property developer and supported by the government. It would remove almost all original elements of the stadium, destroying the monument.

Spend some time polishing this text. It helps to get it right.

Explain why people should care about this issue

Since your audience may be hearing about this issue for the first time, you need to persuade them it’s worth attending a brainstorm about. So explain why it should be important to them.

For example, in 2012 Greece’s ‘image crisis’ was having dangerous consequences for Greeks. I explained in the invitation:

Greece’s global image matters because people outside Greece are making decisions that affect the lives of ordinary Greeks. If these people believe that Greece is only like the headlines and images above, they will not be likely to put the Greek people first.

Furthermore, Greeks are beginning to accept what this image suggests about them – that they are lazy, dishonest and corrupt – and to believe that this is what defines them as a people; that it’s how they all really are. This makes it psychologically much harder for them to get through this crisis.

Lastly, 1 in 5 jobs in Greece are in the tourist industry. Nobody wants to visit a country when they’re being told how messed up and dangerous it is.

Mention the direction you’re considering taking

You’re inviting people to an activist brainstorm, so help people to imagine how they can change things. Even if the approach ends up taking a different turn, you can save time by focusing the discussion from the outset.

Here’s an example from a Campaign Accelerator project we did in 2020. A teacher in the UK called Tony Dale was incensed by the fact that an arms company was running UK schools.. The company had a contract with local government, which was up for renewal. His idea of a solution? Get the contract cancelled:

What happens to the contract between [the local] Council and [the arms company] in 2022 could be down to public pressure. It is an important test case for whether we, as citizens, as progressives, can get the arms trade out of our schools. We should give it a try.

For Omikron, my initial idea was to create productions and do media work that could balance the international narrative. So I included it in the invitation.

We can respond to this image crisis by telling the world the other side of the story. For example, by:

Developing creative content (photos, videos, words, collages, etc.) and spreading them internationally, to show that although life in Greece today may be difficult, the country is not a war-zone / failed state / wasteland of endless poverty and misery!

Working with international media to give them facts and statistics to help them balance their stories and put them in proper context, and create a debate on important issues affecting Greece

… and many other grassroots communications actions that could make a real difference!

Including a direction of your proposed approach will help your brainstorm stay on the right course: problem-solving as opposed to problem-pointing.

Tell them who you are

Especially when it comes to politics and activism, people can be suspicious of your motivations. And many people receiving the email may not know you. They likely won’t show to the meeting if they think there’s a company or established group behind the action — or worse, if they fear they could be used.

But yours is a citizen-led initiative, and you’ve got nothing to hide, so tell them who you are. This was from the brief that started Omikron Project:

Who are we? People who care about Greece. Although our background is in marketing and communications, we have no sponsors, agencies, companies or groups behind us. We are united on one cause – to correct the imbalance and respond to this image crisis… so that Greece has one less problem to deal with!

Ensure you have a few people confirmed

A core of people attracts more, and since it’s a brainstorm there needs to be a variety of ideas to make it worth everyone’s time. Plus, an empty meeting doesn’t look — or feel — good.

So, reach out to people you know to invite them, and make sure there are at least eight to ten people confirmed. The rest should RSVP to you, so you know what to expect going into the call.

Right, now you have your invitation. Send it to everyone you know who could have something to offer, and ask them to invite others who might feel the same. Pick a catchy, explicit subject line — here’s the one from the Omikron invitation:

The image crisis of Greece: how can we respond? A brainstorm THIS Saturday (March 31) at 3pm in Omikron Bar

Don’t publish the invitation on social media, since word-of-mouth is a good filter to getting the right people. If you’ve done the groundwork, they will show.

Step 2: The brainstorm

Prepare it

So the brainstorm doesn’t go all over the place, you need to stimulate people’s ideas with something that goes beyond what you sent them in the invitation.

Research a few examples of the issue you’re raising. And list approaches that others have taken to tackle it — or a related issue. Some online searches is all it takes.

For our Omikron brainstorm, I found headlines that pointed to the problem, and examples of similar campaigns as potential solutions.

Lastly, since you’ll be moderating the call, ask someone else if they can take the minutes.3

Moderate it

- Relax. Your only goal for this meeting is: Is there enough interest? Could these people work together?

- Get the technical stuff right. There’s plenty of best practice out there on how to hold great Zoom calls — beginning with these two posts from Seth Godin4.

- Hold a round of introductions, starting with yourself (max 30 seconds each). Then outline why everyone’s here: to discuss the issue and identify possible approaches.

- Present the issue, covering the examples and approaches you prepared. Don’t communicate any goals; give a direction. As you did in the invitation, help people to imagine how they can change things.

- Then get out of the way and open the floor. Try to ensure everyone gets the chance to speak, because often the most competent people have the least to say. It’s also vital to not let anyone hijack the discussion5, which wastes everyone’s time (what Sanders organiser Zack Exley calls ‘The Tyranny Of The Annoying’)

- Keep the meeting light and informal. If it doesn’t seem like working with these people is fun, no-one will want to come back.

- Leave politics out of the call. Keep the focus on the issue at hand.

- Whenever there’s a pause, or the group gets blocked, highlight another potential approach that you prepared before the call.

Step 3: The follow-up

- Right after the meeting, create an online space6 (even a mailing list will do) where people can continue the conversation, and post links that they mentioned during the meeting. You want to encourage people to share thoughts with the wider group, rather than channeling everything through you. Only invite people to the online space that have taken the time to attend at least one meeting.

- Write up the minutes: a summary of the ideas, links, examples and thoughts that people mentioned during the meeting. Send them to all who attended, and in the same email invite them to the next meeting, which should happen within ten days.

- Send the minutes to anyone you invited to the first meeting who didn’t make it, saying there’s still a chance to get involved if they want to (but if they don’t respond, don’t contact them again).

- Hold the second meeting, which is more focused and solutions-oriented.

As you have more meetings, people will drop off; others may come in and out. But you should be able to assemble a core team who will see the project through.

And then you can start building a real campaign.

Summary

OK, we’ve looked at how to build a team around a cause. Let’s reiterate:

- Invite people. Schedule a Zoom brainstorm to discuss the issue that bothers you. Explain why people should care about it. Mention the direction you’re considering taking, and who you are. Confirm a few people ahead of time so you’re not alone. And ask everyone to invite others who might feel the same.

- Prepare and moderate the brainstorm. Research a few examples of the issue, and of possible approaches. On the meeting day, hold a round of introductions and present the issue. Then get out of the way and let people speak.

- Follow up. Create an online sharing space for the team. Send them the meeting minutes. Organise another, more focused call within ten days. And continue from there.

If this all sounds crazy to you, consider this. Two months ago my wife Olga was despairing at the lack of schooling options in our city. Could it be possible, she wondered, to explore building our own school?

So she applied the method above, starting by inviting people to a Zoom brainstorm who she thought might be interested. And today she’s put together a talented core team, with deep experience in establishing schools. They have done a wealth of research, made links across the country, surveyed nearly 1000 parents in our city to understand their needs, and have 450 (!) people who have offered to help.

It’s true that after their first few online meetings, Olga met many of the core team in person. And there’s no getting around it — Zoom is not a substitute for face-to-face interaction.

But if your focus is local activism, then meeting in person is easy. And if it isn’t, you can still make magic happen. The remote work revolution proves it.

Notes

1: I’m using ‘Zoom’ here as a stand-in for videoconference tools in general. As of writing, it’s still got the best call quality and is easiest to use.

2: With the free version of Zoom, there is a 40-minute limit for calls with more than two parties. Using a Personal Meeting ID ensures everyone can rejoin the meeting at the same URL after the time limit is up. Or you can try to get around the 40-minute limit with this tip (I haven’t tried it).

3: Or: Record the call with your phone’s voice recorder (something much easier to do over Zoom than in an in-person meeting) so you can write up the minutes after. Do tell the attendees that you’re making a recording, and what you’ll use it for.

4: If you’re interested in more on this, Seth Godin has a fantastic podcast episode about Zoom and where it’s going. I’ll expand on how this relates to us as activists in a future post.

5: One way to avoid this is to limit speaking time to 2–3 minutes, and politely cut people off when their time is coming to a close. This ensures a fairer environment for everyone.

6: For Omikron Project we used a private Facebook group. But in these days of surveillance capitalism I’d prefer a simple mailing list. Telegram, Signal, or even Slack are also options, though recently we’re realising the benefits of asynchronous communication. Anyway, all platforms have pros and cons, and there’s no need to go into them all here.

Thanks to Nasos Koroupis, who gave me valuable advice in 2012 on brainstorming before the first Omikron meeting, that I still use today.