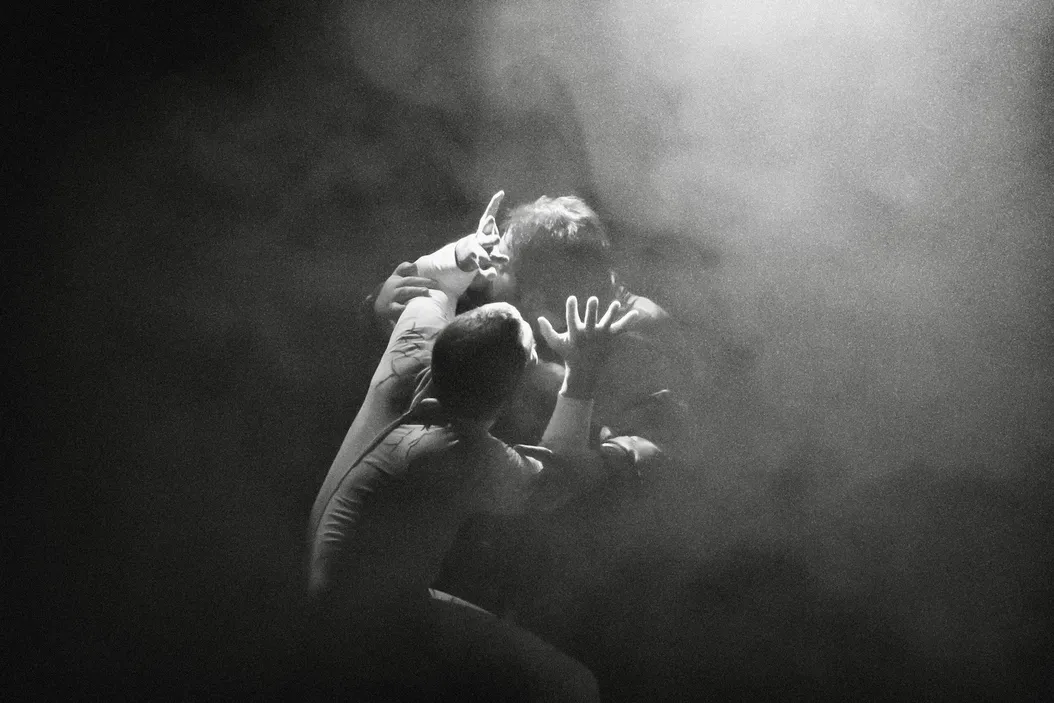

Three real-life disasters

1:

A group is running an on-site training, to prepare its activists for an anti-corruption campaign. Engagement is low, until a participant points out a gender imbalance in the people leading the event.

Bang! The room erupts into argument over gender representation, against the organisers and between participants. The conflict becomes all anyone can remember from that weekend.

2:

A group lives in a city with poor healthcare options. So they're planning to build an alternative clinic. One day, frustrated by the lack of progress and endless discussions, the group's leader proposes taking decisions faster. The other members accuse her of authoritarianism.

Crash! The group becomes mired in discussions and 'therapy' sessions. Six months later, the clinic is still nowhere near completion.

3:

A group is ready to launch a digital campaign against air pollution, that has been months in the making. Some members now complain that the campaign is using commercial tools, like Twitter and Slack. They say this serves the interests of power. And the campaign should adopt open source tools instead.

Wallop! A bitter fight ensues between members over principles vs pragmatism. The campaign ended up foundering.

* * *

These conflicts all happened. And they occur all the time in activist groups.

It's more than a disagreement. It's an implosion.

What's going on here? And as an activist organiser, how can you avoid it happening to your campaign?

A post-mortem

The campaigns above all had some things in common:

- The organisers didn't make it clear why and how the campaigns were planning to confront the Establishment

- There was a lot of discussion, and little action

So at the time they imploded, the campaigns were starting to feel theoretical. More like a discussion forum than an activist project.

In this context, when a person raised a reasonable concern (on gender imbalance, or on which tools the campaign is using), it ignited a firestorm. Instead of aiming at the Establishment, the activist energy turned inward. It had nowhere else to go.

In the first example, the group's leadership became, for the dissenters, a totem of gender inequality. In the second, that symbol was authoritarianism. And in the third, surveillance capitalism.

And it all went downhill from there.

It's not that you have the wrong people

I used to think that a campaign implosion like this was a sign you had the wrong mix of skills on the team.

But the more I've seen this problem, the more my views on it have shifted. True, there will always be people who don't fit in your team, and who should better spend their energy elsewhere. (In the book 'Rules for Revolutionaries', organising guru Zack Exley calls this "the tyranny of the annoying".2)

And it's always sensible to target, rather than accept everyone who shows up, into your core team.

But it's more interesting to see how to convert as many people as possible into willing activists for the cause.

It's not about being inclusive. It's just good strategy.

The answer lies in how well you:

- define the core features of your campaign, emphasising how the Establishment is your target, and why

- provide external-facing action for the team. Make them feel they're progressing towards confrontation with the Establishment

Own your campaign's core features

Core features are what participants need to see in a campaign. They make it attractive for people to join, and easy to follow. The campaign should:

- Be about addressing an injustice that members are outraged by

- Have as its ultimate goal something realistic and achievable, with the potential of seeing justice done

- Give members the belief that they are part of something historic; a battle bigger than the campaign

- Have a plan that's easy for members to follow. The campaign itself should be simple for new members to join

To avoid implosion, you need to propose the core features, and agree them with the team.1

Because if you don't, dissenters will define them for you. And there will be a good chance that the target will be what's in front of their face: you, and the team members on your side.

What could have happened instead

To show you what I mean, see the table below for the case of the first group. It suggests how the dissenters defined each core feature, which resulted in a mess.

And how the organisers could have done the same, to prevent the collapse.

| What happened (defined by dissenters) |

What should have happened (defined by organisers) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Issue that members are outraged about | The organisers don’t respect gender balance | The Establishment (personified by X) is corrupt |

| Achievable ultimate goal | The organisers are publicly shamed and admit wrongdoing | X stops their corrupt activity and compensates victims |

| Belief that the campaign is historic | Gender equality – yes | Corruption – yes |

| Plan that’s easy to follow | Speak up and make a ruckus | Follow organiser’s campaign steps |

Or take the second example. The campaign had positioned itself, towards its members and the public, as a project to build an alternative clinic.

But while this indeed was its ultimate goal, from a messaging point of view the organisers got it back-to-front. People get more fired up about what's wrong with the existing system than an abstract alternative solution. And even more so when you personify your target. So the group would have done better to show its members who they should be mad with, and why.

It could have, say, infused its campaign material with photos of the health minister responsible for the mess the city's hospitals were in. Plastered the walls with quotes from the minister at every meeting. Made public statements about the rot of the medical system... while building the alternative.

Likewise with the group in the third example. It could have positioned the worst polluter as the reason the campaign exists. While pushing its own solutions.

The key point is: every chance you get, keep your team's attention on the Establishment and how you're going to confront it. Because that's where it belongs.3

Idle hands do the devil's work

But to avoid implosion, you can't stop there. Throughout the campaign, you now need to give your team the feeling they're progressing in their challenge to the Establishment. And that they can win.

This means organising external-facing actions, from as early in the campaign as possible. Don't worry if you're not ready to launch the campaign proper – hold a creative protest or an event. Even a team-building measure.

But vitally, don't get stuck in your cave having meetings, trainings, strategy sessions. Get out there and confront openly.

Because it will give you valuable data for your campaign, and test your organising capacity. But especially because it will prevent your people turning inward.

TL;DR

Everyone in your team has activist energy. A desire to help make change happen.

You have to harness this energy, and direct it. Otherwise it can bite you in the ass, and rip your campaign apart.

Seize it by defining and agreeing the core features for your campaign – what every activist project needs for success. That means: an issue that members are outraged about, an achieveable ultimate goal, a belief that the battle is historic, and a plan that's easy to follow.

Then keep the team busy with external-facing actions. So navel-gazing, and the destructive chain reaction it can provoke, never has a chance to set in.

Notes

1: The coordinated do-ocracy model is a good way to do this.

2: ‘The tyranny of the annoying’ refers to people who want to use precious time spouting their political beefs rather than getting to work. Exley says they should not be tolerated and should be pushed out promptly.

3: Am I suggesting that organisers should be immune from criticism, or that team members should never try to improve their internal processes? No! But it's about balance, and timing. If a member's only feedback is about how processes can be improved, that member is likely not valuable to the goals of the campaign. There’s a reason Internal Process Optimiser isn’t one of the three desired skillsets for an effective campaign. As ever, though, it's a judgment call for you as the organiser.