“Shit,” I thought.

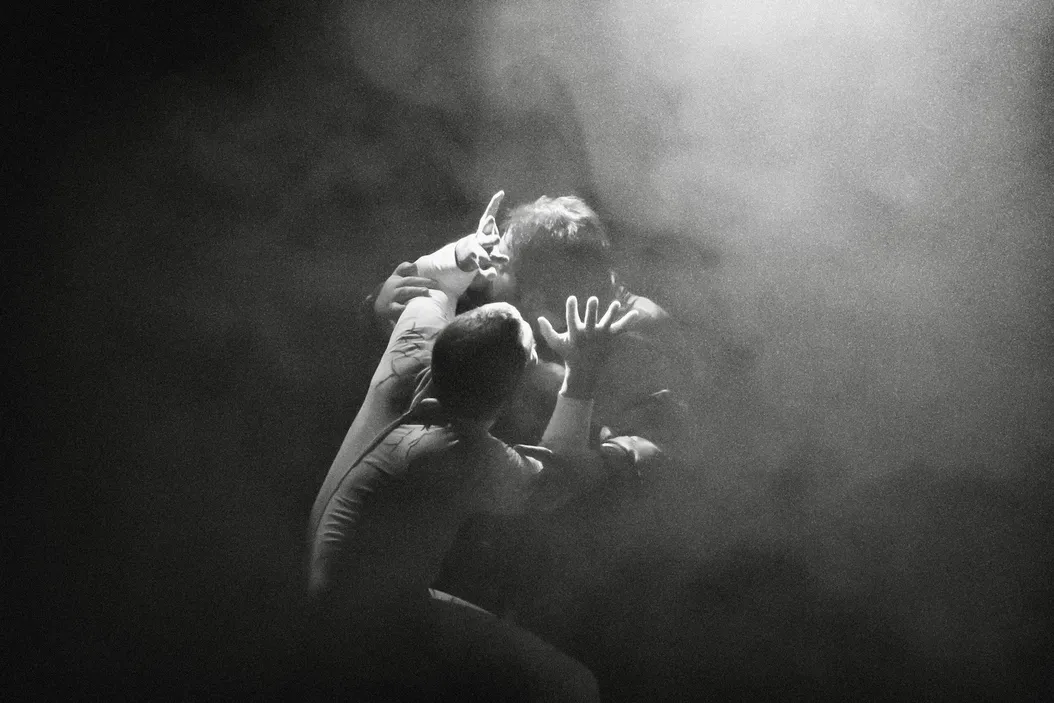

It was 2009, in Brussels, two weeks before opening night. The piece was Shakespeare’s Othello, and I was playing the titular character. Three hours of high emotion on stage, culminating in my smothering my co-star before killing myself.

OK, it was only a community theatre show. But it was a passion project, and I took it seriously. I’d been rehearsing for months, through every lunch break and commute and evening and weekend. I knew every line and the origin and meaning of every line. I’d prepared for this like the obsessive madman the Othello character became.

But something was missing. My performance felt mediocre. I was acting, but not connecting with the text.

And this grey morning I was at a workshop in a drab theatre hall with the acclaimed director Andrew Visnevski, to try to figure out what was wrong. And the advice he’d just given me was:

You need to get yourself out of the way.

Now I was more frustrated than before, and panicking. What was I supposed to do with that response? Thanks a bunch Andrew, I thought, as I left the hall.

But that night, it clicked. I understood what he meant: that there was too much me in my performance. That I was enjoying being on stage, being Othello… when what I needed was to play Othello. I wasn’t giving the character room to breathe, because Mehran was dominating it.

My ego was driving me. It was getting in the way of the work, of telling the story. I needed to rein it in. And so I did.

Andrew’s advice changed my performance. I won an award for Othello. And doing those 11 shows was one of the creative highlights of my life.

For that time, at least, it was Work: 1; Ego: nil.

* * *

Everyone’s a celebrity

I’m telling you this because we live in a peculiar moment. A confluence of things are making our egos drive us more than ever.

I’m no expert on why, but I can guess. Cultural shifts, fed and exacerbated by the ubiquity of social media, have brought us to this point.

As tech philosopher Jaron Lenier notes, social media algorithms reward us when we do what they want. So that’s what we end up doing. Boosting the platforms’ share of global attention by giving more of ourselves. Generating controversy. Waging online wars.

And video takes this to another level. When I was at university, video streaming was something only the fastest connections and computers could handle. Uploading was an overnight deal. No longer: see TikTok and smartphones. Today we have a stage in our pockets, and we can be the star whenever we want.

And with over 40% of the world’s population on social media for much of every day, the impact of these shifts is global. We curate our public identities, while converging into the same online persona.

“We are all celebrities”, as Richard Seymour said in The Twittering Machine.

And being a celebrity brings ego with it.

Ego both helps and harms your activism

Activism has always required a large dose of ego. You have to be somewhat vain, somewhat audacious, to think you can tussle with an established power and make change happen.

I’m no exception to this. Ego is one reason I wanted to apply my private sector skills to not-for-profits when I lived in Brussels. I thought it would be easy, and I enjoyed being seen as an expert. The first job I applied for in an NGO, I sneered at it, thinking I had nothing to learn (I soon realised how wrong I was).

Ego isn’t always a bad thing, though, because it’s what gets you in the door. Let me jump back to acting for a bit. Here’s Daniel Craig:

The greatest asset to an actor is their ego, but it’s also their greatest enemy. The ego gives you the guts to get up there and do it, but it’s also the thing that scuppers you because you’ve got to act, you’ve got to communicate, you’ve got to think about what the other person’s thinking, not whether you look good.

Ego in activism can be an asset when it pushes you to start a campaign, join a pressure group, sign up to a movement. It only becomes a problem if it remains unchecked in the doing.

It’s in the doing that activism can be a catalyst for ego. Because at its essence, activism is a marketing-oriented activity. Which can mean seeing your ideas, sometimes your image, your words, get spread across the world. All things the ego likes and demands.

And the idea that you’re acting out of moral imperative, a sense of duty, only strokes the ego more. Because it reinforces the idea that you’re right.

A runaway ego harms your judgment, affecting your impact.

In an age of permissionless leverage, judgement, not work, determines success and failure.

— Naval (@naval) February 24, 2021

Good judgement is the product of a calm and curious mind, reasoning without motivation and attachment.

Whatever strengthens your ego weakens your judgement, and ultimately, your success.

But it can also blow things up. In my career I’ve seen the wreckage ego can cause, far too often. I’ve seen NGO directors almost coming to blows over who would sit next to the government official at a press conference. Internal fallouts about whose name is on the credits. People who don’t want to vote for what they believe, fearing how their peers will perceive them.

And, unfortunately, I’ve brought on many of these situations myself, when my ego has created friction.

The conundrum of our time: WTF to do about it

When we rein in our egos, the work wins.

It was straightforward for me to do this with Othello, because I was literally playing a different role. On that stage I was no longer me, but a general in 16th century Venice.

But what can we do when our activist work is bound up with our identities? When we’ve reinforced that identity with every social media status update? When our faces are out there for all to see, campaigning on a video, expounding into a microphone on a profile pic?

How do we get ourselves out of the way, and focus on the work?

A few things you can do to put your ego on the back seat

I am far from a good example here, but here are some practical tips that could help.

Step zero: acknowledge you have an ego because you’re human. Dispel the notion that you’re ego-less, altruistic, a great listener, ever open to compromise. Don’t fool yourself, friend; your ego helped get you involved in activism in the first place. And be glad it did.

Turn off Zoom self-view

Videoconference without yourself on screen. It focuses your energy on the people you are talking to, as real life. Not on whether you look good. (H/t Seth Godin.)

This is more effective than you think. Try it.

Picture the beneficiary

Take a photo that symbolises what your campaign is fighting for. Whether it’s a person, a panda or a piece of land. And put it up on your wall or your desktop.

When I develop strategy for clients, I include such a photo in the document. It might sound corny, but it works.

Choose your battles

When was the last time you ended a tense discussion with ‘let’s agree to disagree’? Make it more often. Instead of trying to convince the other party you’re right.

Watch what your mind is doing

The mind is a muscle that you can train like any other. Observe yourself from a distance, through meditation. Cultivate your curiosity. Invest yourself in upgrading instead of defending your ideas.

Outcome over ego. pic.twitter.com/hPG3fd6RFg

— Shane Parrish (@ShaneAParrish) April 12, 2020

You’ll see when your ego is infecting your judgment. And it’ll be easier to take remedial action.

Split work and personal

Keep an iron distinction between work time and personal time. Because when they bleed into each other, it’s easier for ego to creep in and make mischief.

This is harder to do with online work, I’ll grant you. But you can still have a weekly chill-out session for the team without shop talk. And keep private chats for after hours.

Have a life outside activism

Related: don’t make your activist project your life. You’ll over-identify with it. You’re an activist citizen, sure, but be sure to also be a mother, a sister, a friend, a tennis player, etc.

Get outside for real

Go for a walk, spend time in nature. It’s impossible to feel ego with the sea before you, or looking up at a mountain.

No nature around? Try art.

And if you find yourself frustrated that you can't make something equally beautiful, well, you might need more help than an activism newsletter can provide.